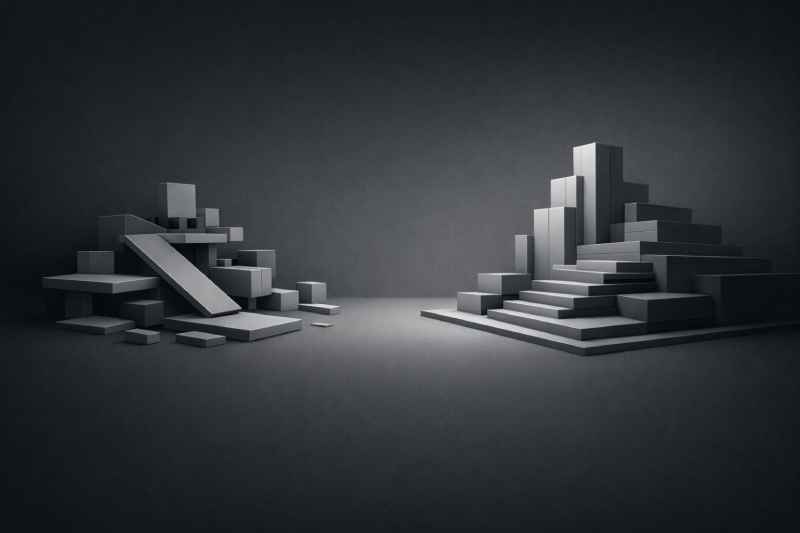

The Trade-Off Between Speed and Structure

Date: December 2025 | Author: Orie Hulan | Reading Time: 6 min

Organizations often operate under time pressure. Goals are defined, deadlines are set, and success is measured by how quickly something works. In those moments, speed becomes the dominant signal of progress. If an outcome is delivered fast, it is often seen as the right outcome.

The problem is that speed rarely comes without trade-offs. When results are required immediately, many of the steps that support long-term stability and structure are skipped. What initially looks like progress often becomes the source of complexity later on. This is how many siloed systems are created.

In most data and integration scenarios, systems actually share a lot of common structure. Fields are similar. Files follow comparable patterns. Differences tend to be incremental-a column here, a naming convention there, a slight variation in business rules. On their own, these differences do not justify entirely separate solutions.

But when strong standards or centralized frameworks do not exist, the easiest response is to treat each case independently. Each vendor, source, or integration becomes its own package, built and deployed separately from everything else. That approach moves work forward immediately and avoids long design discussions. It solves the problem that is directly in front of you. It also quietly sets up future complexity.

At first, these stand-alone processes feel like a win. They are isolated by design, so changes in one system do not risk breaking another. When something goes wrong, it is usually clear where to look, and the blast radius is limited. In high-pressure environments, that simplicity matters-and for a while, these systems work just fine.

The issues start to surface as the number of one-off processes grows. The same problems exist in multiple places, implemented slightly differently each time. Fixes get duplicated. Enhancements have to be repeated. Documentation becomes critical-and often insufficient. Over time, understanding how things work lives more in peoples heads than in shared references, which makes onboarding harder and troubleshooting slower.

This is often reinforced by reactionary environments. Centralized systems introduce their own complexity: when systems are connected, changes carry more risk. But teams operating in constant urgency rarely have the space to build safeguards like testing, isolation, or controlled execution paths. Instead, quick fixes dominate. Those fixes reinforce siloed design, and the system never gets the opportunity to mature into something resilient.

There is also a cost that tends to be overlooked. Centralized systems require ownership-standards, structure, and ongoing coordination. They require alignment around how data arrives, where it lives, and what assumptions can be made about it. That work is easy to undervalue because it does not usually produce immediate, visible wins.

Over time, the impact shows up in the data itself. Fragmented systems make unified views difficult. Normalizing across sources becomes expensive. More advanced analysis depends on specialized knowledge of each individual pipeline. The value of the data still exists, but it is locked behind structure that was never designed to converge.

None of this means one-off solutions are inherently wrong. Reactionary systems are understandable. Speed matters, and isolated solutions solve real problems. But speed has a cost, and so does structure. The difference is when that cost is paid, and by whom. Fast outcomes and sustainable systems pull in different directions, and every system eventually reflects which one was prioritized.